5 years of investment learning

Five years of investment, mistakes and learning summarized in clear principles to invest with rigor, lucidity and discipline in a complex market.

More than five years ago, I began my journey as an investor with enthusiasm, a bit of theory, and mostly a lot to learn. Today, after hundreds of hours reading financial reports, costly mistakes, interesting gains, and deep reflection on what it really means to “invest intelligently,” I want to share my learnings. What you will read here is not a miracle method, nor a promise of returns, but a condensed set of concrete insights and rigorous practices that have transformed the way I approach investing.

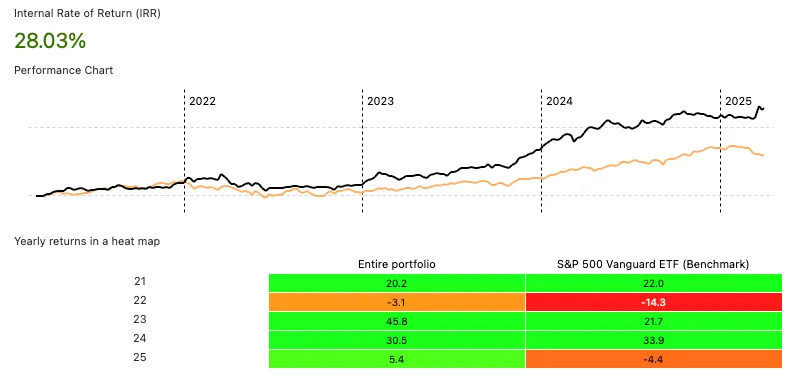

My chart starts in 2021 because my investments from 2019 to 2020 were passive in BRK.B and ETFs (SP500 & TSX). I really started active investing after 2 years of learning.

Reading Financial Reports Like a Detective

A good investor doesn’t just read a financial report they dissect it. Every footnote, every accounting change, every line in the proxy statement can contain crucial information. I’ve learned that details aren’t decorative they often spark ideas or sound alarms.

The notes to the financial statements are a gold mine. They might reveal, for example, that a company has changed its depreciation method, which can artificially inflate net income. In 2010, Apple modified an accounting standard this seemingly isolated detail had a significant impact on its income statement.

Retrospective Adoption of Modified Accounting Standards:

The new accounting principles led the company to recognize nearly all revenue and product costs for the iPhone and Apple TV when those products were delivered to customers. Under previous principles, the company had to recognize iPhone and Apple TV sales under the subscription method, due to its promise of free future software updates for these products. This meant deferring revenue and costs over the estimated life of the products. With the new rules applied retrospectively, this accounting had a notable impact.

Understanding the differences between GAAP and IFRS standards is critical. The same company can look profitable under GAAP and far less impressive under IFRS, or vice versa.

The proxy statement and annual shareholder letter inform you about governance, executive compensation, and alignment with shareholders. Pay close attention to retroactive stock option adjustments following a share price drop rarely a good sign. This awareness can save you time before diving deeper into a company analysis.

Reading Event Notes: An Overlooked Source of Alpha

Among all sections of a financial report, the note on significant or subsequent events is one of the most underestimated yet often where the future is hidden. These sections, labeled "Significant Events" or "Subsequent Events," reveal recent or upcoming elements not yet reflected in the financial statements.

These events may include winning or losing a major contract, legal disputes, fundraising, acquisitions, leadership changes, or natural disasters affecting operations. They are sometimes disclosed between the end of the reporting period and the publication of the document.

Reading this note can give you a catalyst ahead of the market. Many investors only glance at the headline figures. Identifying a significant event before analysts price it in can offer a critical informational edge.

Example: A small industrial company mentions in its notes that it has signed a $20 million contract with a new European client, not yet recorded as revenue since delivery starts next quarter. The market hasn't reacted because this info doesn’t appear in press releases. For the attentive investor, this may justify an immediate reevaluation of the stock.

Some events may also be negative like product recalls, cyberattacks, or temporary plant closures. It's better to catch these before they are priced in.

These notes also help test management’s transparency. A leader who communicates openly about risks and recent events even unfavorable ones demonstrates healthier governance than one who hides or minimizes information.

Never skip this section. It’s short but crucial. It’s where surprises good or bad are born. In a world where information is currency, this small note can be worth a lot.

The Art of Adjusting Numbers: Accounting is Not an Exact Science

Accounting is a language, but also an art. And sometimes, that art is used to beautify reality. That's why I’ve learned to always “clean” the financial statements to make up my own mind.

Depreciation and impairments can be used to manipulate profits. It’s crucial to recast these items for a clear, comparable view. This helps us know if we’re dealing with a prudent CFO and CEO or with irresponsible or misleading judgment. For example, in the cloud sector, Amazon, Google, and Microsoft all use different depreciation schedules for data centers. One amortizes CPUs, RAM, disks over 4–5 years, another over 7. These accounting differences can distort comparisons if not adjusted.

Some executives use accounting flexibility to record large impairments in a bad year, creating a low base for a rebound the following year a technique called "big bath accounting." Such manipulation isn't obvious without reading the notes to the financials.

Ratios like EV/EBITDA are still overused despite their limitations. This ratio ignores capital expenditures (CAPEX) and thus doesn’t reflect a company’s true economic reality. It can help compare turnaround stories, but for long-term investors, it’s often misleading.

Prefer adjusted metrics like EV/EBIT, EV/NOPAT, ROIC, and ROIIC they capture real operating profitability and invested capital. These indicators tell you whether a business creates real value.

The true test of a good investment is its ability to generate ROIC or ROIIC above the cost of capital adjusted for inflation. This helps avoid value traps.

Never blindly trust the raw figures. Clean them, adjust them, put them in perspective. Accounting is malleable your analysis shouldn’t be.

Building a Credible and Justifiable Investment Thesis

One of the most common traps in investing is building an ambitious thesis... without being able to concretely justify it. A growth projection is worthless if not backed by tangible elements. A good investor must be able to explain how and why a company will achieve the goals laid out in their scenario.

For instance, if you expect 20% revenue growth annually for three years, you need to justify that assumption. This could come from:

Opening new stores or outlets.

Recently signing a major contract with a key client.

Launching a new product or service with solid sales forecasts.

Geographic expansion into a new region or country.

Opening a new factory increasing production capacity.

A confirmed increase in prices or margins, supported by innovation or a dominant market position.

Example: A consumer goods company announces the opening of 50 new stores in Mexico and Brazil over the next two years. Each location is expected to generate $1.5 million in annual sales. This allows modeling predictable revenue growth based on verifiable assumptions.

On the other hand, a thesis based solely on mean reversion, without a visible trigger or catalyst, is fragile. You need concrete and quantifiable elements to justify your key assumptions.

Always ask: “And why should this happen?” If the answer is vague or based on a feeling, dig deeper.

A solid investment thesis rests on clear logic, defensible figures, and a deep understanding of the business model. The simpler your thesis is to explain and justify, the more likely it is to be correct and profitable.

The Importance of Working Capital

Working capital is one of the most overlooked yet critical components of financial analysis. It represents the short-term resources available to run the business: inventory, receivables, and payables. Poor working capital management can destroy a company, no matter how profitable it seems.

Negative working capital can be a great sign in some industries (like retail or fast-cash-flow models) because it means the company gets paid before having to pay suppliers.

Conversely, an uncontrolled rise in accounts receivable or inventory may signal slowing sales, distribution problems, or revenue quality issues.

Good management example: Amazon long benefited from negative working capital, paying suppliers in 90 days while receiving money from customers immediately. This helped fund growth without diluting shareholders.

Bad management example: An industrial company sees inventories surge without revenue growth. This can lead to a cash crunch, storage costs, obsolescence, and even large losses.

Working capital is also an indirect indicator of management quality: a good leader optimizes flows without compromising growth, keeping an eye on payment delays, inventory levels, and receivable turnover.

For investors, monitoring working capital year-over-year (and relative to revenue) helps anticipate liquidity tensions or spot exceptionally efficient companies.

The Time Factor: The Invisible Enemy of Returns

Returns are not just measured in percentage, but in time. An opportunity promising a 100% return might seem attractive, but if it takes 5 or 6 years to materialize, its annualized return (IRR) becomes much less appealing than another more modest but faster investment. Time is an often-ignored factor, yet it directly impacts your overall performance.

Always compare the annualized return (IRR) to the total time required to realize the gain (TRW: Time to Realize the Win). An investment can have a good absolute return but be a poor decision if the TRW is too long.

Example: You invest in a stock at $10, and it reaches $20 in 5 years you've doubled your money. But that’s about a 15% annual return. Another opportunity giving you 40% in 18 months, even if seemingly less “safe,” is much more efficient in terms of capital rotation.

The time factor becomes even more important in concentrated portfolios. Waiting 5 years for each idea ties up too much capital and reduces the number of moves you can make over a decade.

Never make predictions beyond two years. Macroeconomic variables, tech disruptions, and regulatory changes make long-term forecasts too uncertain to be useful. Build theses that can play out within 12–24 months, with a clear exit based on identified catalysts.

Rather than relying on complex DCF models with arbitrary discount rates (2%, 6%, 10%...), use a conservative exit multiple based on industry history or direct comps. This reduces bias and keeps you grounded in market reality.

Example: A company is trading at 5x EV/EBIT, while the sector’s historical average is 9x. If your thesis is a return to the mean over 18 months with stable earnings, you can calculate a realistic, time-bound return.

Remember: Locked capital is capital that can’t be reallocated. A “potentially good” investment in 4 or 5 years carries high opportunity cost if, in the meantime, you miss better opportunities.

A good investment is not only profitable, but quick to materialize. Time is invisible, but it defines your ability to perform over the long term. Learn to factor it in from your first analysis.

Finding EV+ Opportunities and Keeping It Simple

The best investment opportunities are often the simplest. Complexity is not a sign of quality on the contrary, it can mask risks, dilute the investment thesis, and make follow-up harder. My experience has taught me that simplicity is a powerful tool, especially when combined with rigor.

Micro-caps are particularly appealing. Often ignored by institutional analysts, they receive little or no media coverage, and publish short, direct financial reports. You can gain an informational edge simply by reading what most investors neglect.

Example: McCoy Global Inc., a Canadian micro-cap specializing in equipment and services for the energy sector, was long ignored by the market. It owns proprietary technology in a specific niche, has a loyal international customer base, and conservatively manages liquidity. Despite modest market cap, it boasts a net cash position, profitability even in downturns, and a clear intent to create shareholder value, including opportunistic buybacks. Its investor deck is just 15 pages, and reports are concise and transpar...

The goal is to find EV+ situations where expected value is significantly positive, considering risk, time, and uncertainty. To get there, you need a margin of safety buying below your reasonable estimate of intrinsic value. This is the essence of fundamental investing.

A concentrated portfolio (10–12 positions) is ideal. It allows deep tracking of each company, prevents distraction, and keeps quality standards high. To maintain such a portfolio, you only need to find 3 to 4 strong new ideas per year realistic with discipline and structure.

Always ask: why does this opportunity still exist? Maybe it’s overlooked due to size, illiquidity, or a misunderstood temporary event. But if you can’t find a reasonable explanation, be cautious you might be missing something.

Other EV+ examples: Velan Inc., a Quebec-based valve manufacturer, whose acquisition by Flowserve was blocked by French regulators. This caused the stock to drop, despite a solid balance sheet, tangible industrial assets, and a full order book. A typical case where market emotion causes mispricing.

Simplicity allows clarity. It makes tracking more rigorous, errors easier to spot, and analysis more relevant. In an overloaded information world, identifying a simple but misunderstood opportunity is a valuable skill. Keep your process simple but your standards high.

Avoid Overvalued Mega-Caps, Favor Micro-Cap Growth

Buying a mega-cap at more than 20–25 times earnings (P/E) is very expensive, especially in an environment with higher interest rates and limited growth. Yet, many investors seem to have forgotten that.

Historically, companies in the S&P 500 have a 95% chance of no longer being part of the index 25 years later whether due to bankruptcy, acquisition, stagnation, or loss of relevance. Betting on their longevity as a safety guarantee is a mistake.

In contrast, a fast-growing micro-cap, even purchased at a high multiple like 25x, often has better odds of success if the business model is sound, margins are expanding, and the addressable market is still large.

It’s not the absolute level of the multiple that matters, but the underestimated growth potential and the ability to reinvest at high returns. In micro-caps, you often buy before discovery while in mega-caps, you buy after everyone has already paid a premium for perceived safety.

Focus, Discipline, and Humility: The Underrated Pillars

Ambitious investing requires focus. Aiming for 15%, 20%, even 30% annual returns without dedicating significant time is unrealistic unless you're very lucky, and luck is not a strategy. Good performance rests on structured methods, hours of analysis, strong mental discipline… and a healthy dose of humility.

Today’s markets are more regulated, more transparent, and investors are more educated than ever. Databases are widely accessible, and AI and algorithms intensify the competition. Thinking you can beat the market without effort is a dangerous illusion.

Even small caps, once reserved for insiders, are now well-covered by institutional investors, specialized newsletters, or collaborative platforms. To retain an edge, you must be faster, more independent or simply more disciplined.

Discipline means knowing when to say no. Don’t cave to pressure to always be invested. Sometimes the best decision is to wait. For example, holding cash for three months because nothing meets your criteria is more productive than forcing a mediocre investment.

Also, be honest with yourself: few people can actively manage 30 or 40 positions. A concentrated, actively monitored portfolio is often more effective than an overly diversified one where each position becomes blurry. Knowing 10–12 companies in depth already takes significant time.

Long-term investing is often wrongly idealized. Sure, holding a company for 10, 15, or 20 years sounds appealing. But such companies are rare. Markets evolve, cycles shift, competition changes. It’s normal and healthy to sell after 1, 2, or 5 years if the thesis has played out or a better opportunity arises.

Example: You bought a company at 8x P/E with an identified catalyst (restructuring, leadership change, debt reduction), and its multiple climbs to 18 in two years. Even if it continues to grow, your expected future return declines. Selling to reinvest in a more undervalued business is rational not a betrayal of the long-term philosophy.

Lastly, you need humility. Even with all the analysis in the world, you’ll be wrong. And sometimes, you’ll be right for the wrong reasons. Accept it. Learn. Refine your process. What matters is the consistency of your decisions over time not perfection on every pick.

Focus helps you dig deep. Discipline keeps you from drifting. Humility keeps you on track. These three qualities don’t show up in an Excel sheet but they’re essential to perform and endure.

Bet on Good Management, Not Just the Numbers

A company is often the reflection of its leadership team. The CEO, CFO, COO, and board chair are key people whose history, behavior, and strategic intentions must be analyzed. A good leadership team can turn an ordinary business model into a value generator while a bad one can ruin the best ideas.

Do your homework: research their past roles, companies they ran, and the results they achieved. A leader who built a successful company ethically is a good sign. One who jumps between companies every two years without visible results is a red flag.

Listen to their words and watch their actions: earnings call transcripts, shareholder letters, and media interviews are gold mines. Do they own up to mistakes? Talk about sustainable growth or just short-term profits? Communicate clearly or hide behind vague language?

Analyze compensation structure: alignment between executive pay and long-term performance is essential. For example, compensation mostly in options with clear multi-year performance targets is far more credible than a huge cash bonus regardless of results.

Negative examples: some tech firms have retroactively reduced stock option strike prices after stock drops rewarding executives despite strategic failure. Others have handed out massive shares during fundraising, diluting shareholders with no economic justification.

Positive example: in an industrial micro-cap I analyzed, the CEO was the founder, owned over 30% of the shares, took a modest salary, and regularly bought shares on the open market. He rarely spoke publicly but aligned decisions with shareholders at every step. That’s exactly the kind of behavior I look for.

Management is not a secondary factor it can make all the difference. Great management with a bad product may succeed more than bad management with a brilliant idea. Be uncompromising: you’re investing in people as much as in numbers.

Returning Capital to Shareholders: A Key Performance Driver

Returning capital to shareholders is a powerful sign of maturity, financial discipline, and respect for company owners. But like everything else, it’s not the act itself that counts it’s the context, timing, and execution.

Free cash flow (FCF) is a company’s primary tool for creating value. If it can reinvest in projects with ROIC above the cost of capital plus inflation, that’s usually the best use. It means each dollar reinvested returns more than a dollar.

But when growth opportunities dry up or become less attractive, cash should be returned to shareholders via dividends or share buybacks. This is a strategic choice that must reflect the company’s real economics, not financial trends or attempts to boost stock prices artificially.

Buybacks only create value under one condition: when the stock trades below intrinsic value. Otherwise, the company wastes capital, reduces P/E artificially, and weakens the balance sheet.

Bad example: a tech company that peaked post-COVID spent $500 million on buybacks at over 40x earnings. Two years later, the stock had dropped 60% and the company was unnecessarily in debt destroying value, credibility, and flexibility.

Good example: NVR Inc., a U.S. homebuilder, is a model of buyback discipline. It pays no dividend but has used FCF for opportunistic buybacks for over 20 years. As a result, its share count is down over 75%, with a conservative financial structure and exceptional profitability. NVR is a benchmark in rational capital allocation in a highly cyclical sector.

Dividends are often underrated in modern investing. Yet they are a major long-term performance driver, especially when reinvested. A company that pays steady, growing dividends while maintaining healthy debt levels shows it can generate real, sustainable cash.

Beware of cyclical sectors like mining, energy, or construction. In these industries, cash flow fluctuates massively with cycles or commodity prices. Here, it’s better to build reserves or pay variable dividends than commit to buybacks that could be disastrous in downturns.

A good return of capital is an act of responsible management. It reflects the company’s confidence in its ability to generate cash and in its own valuation. But it must be grounded in rigorous analysis, not superficial signals.

Learn, Document, Repeat

Investing is also about continuous learning and good tooling. An investor never stops improving, because each market cycle, each company, each mistake brings new lessons.

Keep a structured personal database: whether it’s Excel, a custom app, or dedicated software document each investment idea, with your initial assumptions, catalysts, risks, updates, and results. This lets you measure progress and learn from real mistakes.

Rely on official sources: annual reports (10-K), quarterly reports (10-Q), proxy statements (DEF 14A), call transcripts, SEDAR or EDGAR filings. Avoid platforms that summarize or interpret data without transparency about their methods. A simple misread on Seeking Alpha, for instance, could make you miss a critical detail.

Top 5 must-read books for beginners:

Valuation (7th edition)

Value Investing

Pitch the Perfect Investment

Financial Intelligence

The Personal MBA

Shareholder calls are gold mines: you’ll hear management discuss their operational reality, concerns, sector trends, and competition. These are often the first places to mention margin pressure, rising logistics costs, or regulatory changes coming to a country. Shareholder calls are a better macro source than economist reports they speak directly to real-world business conditions.

Example: during a quarterly call from a Canadian transport firm, the CEO briefly mentioned temporary restricted access to Vancouver’s port due to construction. This wasn’t in the written report but significantly impacted their logistics segment the next quarter.

Finally, develop a repeatable process. Analyzing a new company should follow the same steps as the last. It reduces bias, boosts rigor, and gives useful comparison points.

Learning is a cumulative advantage. The more structured your learning and documentation, the sharper your judgment becomes over time.

Final Rules, Personal Philosophy, and Core Beliefs

Unadjusted accounting ratios can be more harmful than helpful. Always do your own math.

You don’t need to be intellectually flashy the goal is to make money with consistency.

Always look for EV+ decisions with a margin of safety this remains your compass. Never stray from it.

Never invest in something you don’t understand.

Always ask: why does this opportunity exist? Why are you right and the market wrong?

A good write-up rarely exceeds 5 pages. It’s not about length, but clarity.

Don’t try to be the smartest in the room. Try to be the most clear-headed.

Conclusion

After five years of active investing, one thing is clear: this craft demands rigor, realism, and humility. It’s not about always being right but about avoiding big mistakes, uncovering economic truth behind the numbers, and taking the time to do things right.

Keep your process simple, stay curious, challenge yourself, and remember doing nothing is often an excellent decision.

In a noisy world, the disciplined and quiet investor still has every chance.

Max

Hats off. You've learned so much so quickly. You'll do very well going forward.

Great article!