The Rapid Rise and Fall of Adeptus Health: A Working Capital Cautionary Tale

A story that highlights the importance of working capital. What are the reasons why companies need to track working capital and how can a bad business model lead to bankruptcy?

In my opinion, working capital is a topic that is not talked about enough in the field of investment. In many sectors of activity, working capital is very important, and poor management by the CFO and management can quickly become catastrophic.

Rather than explaining why this is crucial using several examples and calculations, I suggest the story of Adeptus Health. I could have chosen one of the hundreds of business stories that went bankrupt because of their working capital, but Adeptus Health is more original. Their idea seemed good, but the business model was not suitable for this sector.

Adeptus Health was a start-up that has grown by more than 50% annually. In 2012, their revenue was $81 million. In 2015-16, their revenues rose to over $420 million in less than 4 years.

I’m not referring to negative working capital. It will be for another occasion. Nevertheless, negative working capital can quickly become catastrophic. But beware of companies that have negative working capital in strong growth. If growth slows, or worse, if sales decline. The company may need to find money quickly to settle accounts.

I recommend you read the working capital series of "CFO Secrets" and every others post. It is a valuable source on accounting, full of authentic stories. I enjoy reading it every week.

In the complex and often inefficient landscape of American healthcare, disruptive models that promise convenience, better service, and strong financial returns inevitably capture the imagination of patients, providers, and investors alike. For a time, Adeptus Health Inc. seemed poised to be one of the great success stories in this arena. As a pioneer and the largest operator of Freestanding Emergency Rooms (FSERs), Adeptus rode a wave of rapid expansion, culminating in a successful IPO in 2014 that saw its valuation soar. The company's modern facilities, shorter wait times compared to traditional hospital ERs, and strategic partnerships painted a picture of innovation fundamentally reshaping emergency care delivery.

Yet, just a few short years later, this high-flying enterprise came crashing down, filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in April 2017. While various factors contributed to its demise, including competitive pressures and the complexities of healthcare reimbursement, a critical and ultimately fatal flaw lay at the heart of its operations: a profound failure to manage its working capital. Specifically, Adeptus Health's inability to convert its impressive, high-dollar billed revenues into actual collected cash in a timely manner created a liquidity crisis that its rapid growth could not outrun. The story of Adeptus Health serves as a stark and valuable lesson for investors and business leaders on the paramount importance of understanding and managing the operational lifeblood of any company – its working capital – lest impressive top-line figures mask a fatal underlying fragility.

The Genesis of an Idea: Targeting ER Inefficiencies

The concept behind Adeptus Health tapped into a genuine pain point in the US healthcare system: the often frustrating and inefficient experience of visiting a hospital emergency room. Patients frequently faced long wait times, crowded conditions, and inconvenient locations, particularly those living in burgeoning suburban areas underserved by large hospital campuses. Adeptus proposed a solution: build and operate fully equipped emergency rooms, staffed 24/7 by board-certified physicians and emergency nurses, but located independently from hospitals, often in easily accessible retail-like settings.

These FSERs were designed to offer the same level of care as a hospital ER for most emergencies – equipped with diagnostic tools like CT scanners, X-rays, and ultrasound, along with onsite laboratories – but without the attached inpatient beds. The value proposition for patients was clear: faster access to high-quality emergency care in a more comfortable and convenient environment. For the business model to work financially, Adeptus relied on billing patients and their insurers at rates comparable to hospital ERs, which are significantly higher than those charged by lower-acuity "urgent care" centers that typically handle less severe conditions.

Founded in 2002 in Lewisville, Texas, the company initially grew cautiously. However, recognizing the potential scale of the opportunity, it began an aggressive expansion phase in the early 2010s. The model seemed particularly viable in states like Texas and Colorado, which had regulations more favorable to FSERs and large populations experiencing rapid growth. Adeptus focused heavily on creating a positive patient experience, hoping word-of-mouth and convenient locations would drive volume.

Furthermore, Adeptus pursued a strategy of partnering with established, reputable hospital systems. These joint ventures (JVs), such as those formed with UCHealth in Colorado, Dignity Health in Arizona, and later Ochsner Health System in Louisiana, offered several advantages. They lent Adeptus the credibility of a recognized hospital brand, potentially reassured patients about the quality of care, and, crucially, were intended to improve relationships with insurance companies by bringing the FSERs into the hospitals' existing network contracts. Under these JV arrangements, Adeptus typically built and managed the day-to-day operations of the FSERs, sharing the financial results with its hospital partner.

The IPO and the Acceleration of Growth

The combination of a seemingly disruptive model addressing a clear market need, rapid facility rollout, and strategic partnerships created significant buzz in the investment community. Adeptus Health successfully completed its Initial Public Offering (IPO) in June 2014, raising substantial capital. The offering was well-received, and the company's stock price climbed significantly in the months following, briefly pushing its market capitalization above the billion-dollar mark.

Flush with cash from the IPO and emboldened by market enthusiasm, Adeptus doubled down on its expansion strategy. The number of facilities under its management grew at a blistering pace, reaching over 100 locations across multiple states. The company projected continued strong revenue growth, driven by the increasing volume at existing centers and the steady stream of new openings. On the surface, Adeptus appeared to be a phenomenal growth story, successfully carving out a lucrative niche in the vast healthcare market. Investors cheered the rising revenues and the expanding footprint, seeing Adeptus as a prime example of healthcare innovation delivering both patient benefits and financial rewards. However, beneath the impressive top-line figures, the operational gears responsible for converting those revenues into sustainable cash flow were beginning to grind dangerously.

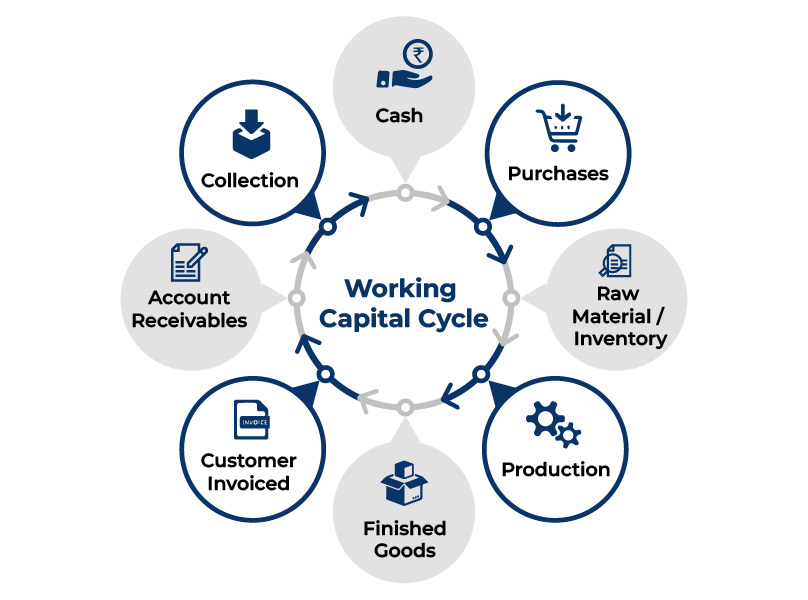

The Working Capital Quagmire: When Revenue Isn't Cash

The fundamental challenge for any business, particularly one growing rapidly, is managing the cycle of converting resources into cash. This is the essence of working capital management. For Adeptus Health, the critical bottleneck emerged in its accounts receivable (A/R) – the money owed to it by patients and, far more significantly, by insurance companies.

Adeptus's high revenue figures were predicated on its ability to bill and collect at rates similar to hospital ERs. This proved far more difficult in practice than anticipated, for several reasons:

Payer Resistance and Out-of-Network (OON) Challenges: While partnerships aimed to bring facilities "in-network," many Adeptus locations initially operated OON for numerous insurance plans. This allowed Adeptus to bill higher rates, but insurers increasingly pushed back. They contested the appropriateness of hospital-level ER charges for services delivered in a non-hospital setting, implemented stricter review processes, down-coded claims (paying at a lower rate for a supposedly less complex service), or simply delayed payments significantly while disputes were resolved. Even for in-network claims, reimbursement for complex emergency care often involved lengthy verification and negotiation.

Patient Responsibility and Surprise Billing: The rise of high-deductible health plans meant patients were responsible for a larger portion of their medical bills. Many patients visiting Adeptus FSERs were unaware they might be treated as OON or that the charges would mirror expensive hospital ER rates, leading to "surprise bills" amounting to thousands of dollars. This generated patient disputes, negative publicity, and a significant increase in uncollectible patient balances (bad debt).

Billing Complexity and Inefficiency: Managing the billing and collection process across dozens of facilities, multiple states, numerous complex hospital JVs, and countless different insurance plans required a highly sophisticated and efficient operation. Adeptus, focused on rapid physical expansion, struggled to scale its back-office billing and collection infrastructure effectively. Errors, delays in claim submission, and inefficient follow-up processes further exacerbated the collection delays.

The direct consequence of these factors was a dramatic and alarming increase in Adeptus Health's Days Sales Outstanding (DSO). While a healthy DSO in healthcare can vary, Adeptus saw its collection cycle stretch far beyond reasonable norms. It was taking the company many months, sometimes well over 100 or even 150 days on average, to collect cash for the services it had provided and recognized as revenue.

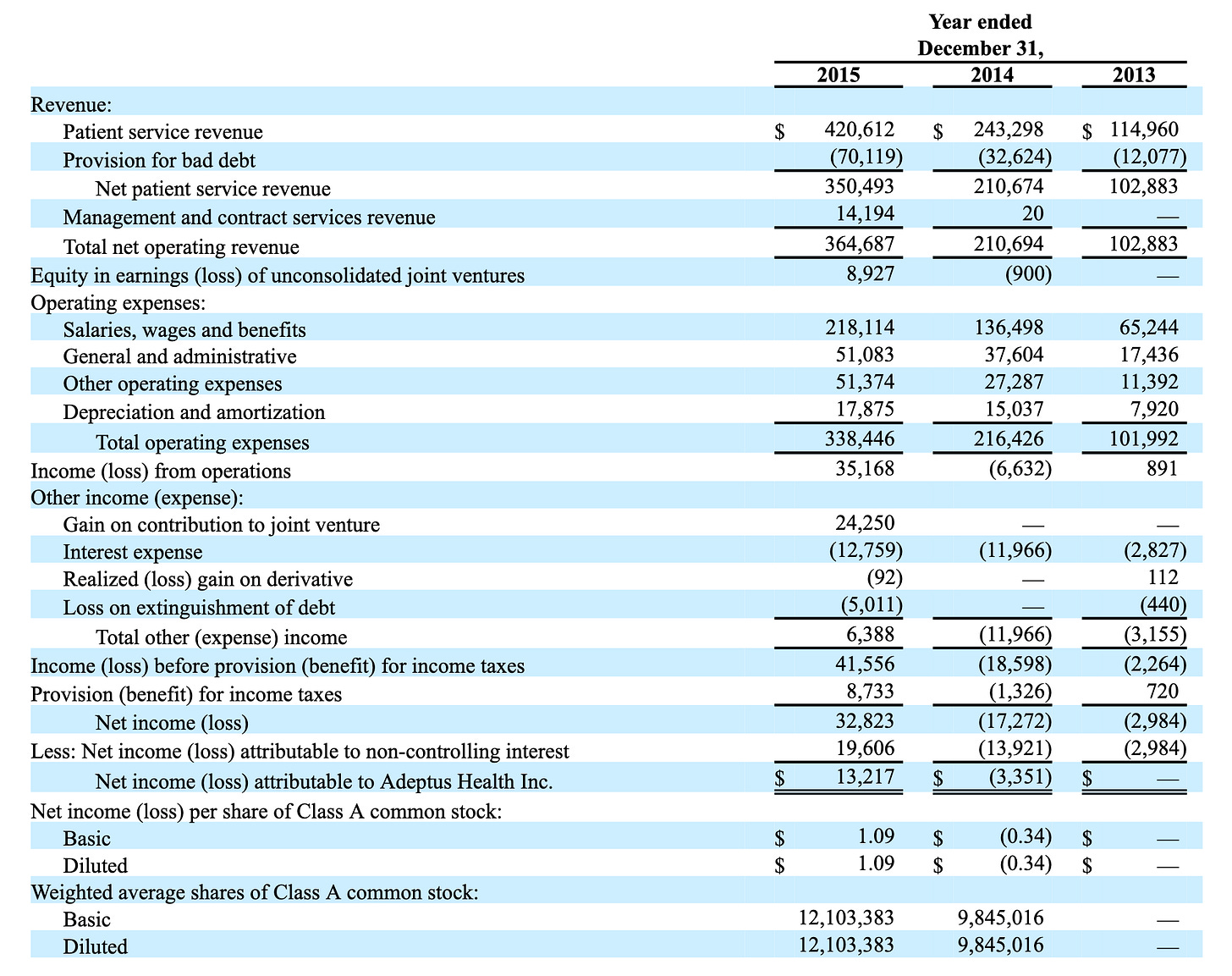

This ballooning A/R balance acted like a giant sinkhole for the company's cash. Hundreds of millions of dollars were effectively trapped – recognized on the income statement as revenue, contributing to impressive top-line growth figures, but unavailable as actual cash to run the business. This cash was desperately needed to pay the high fixed costs of its numerous ER facilities (physician and nurse staffing, medical supplies, rent, utilities, equipment maintenance) and to fund the ongoing construction of new centers. The company was generating revenue on paper but starving for the actual cash those revenues represented.

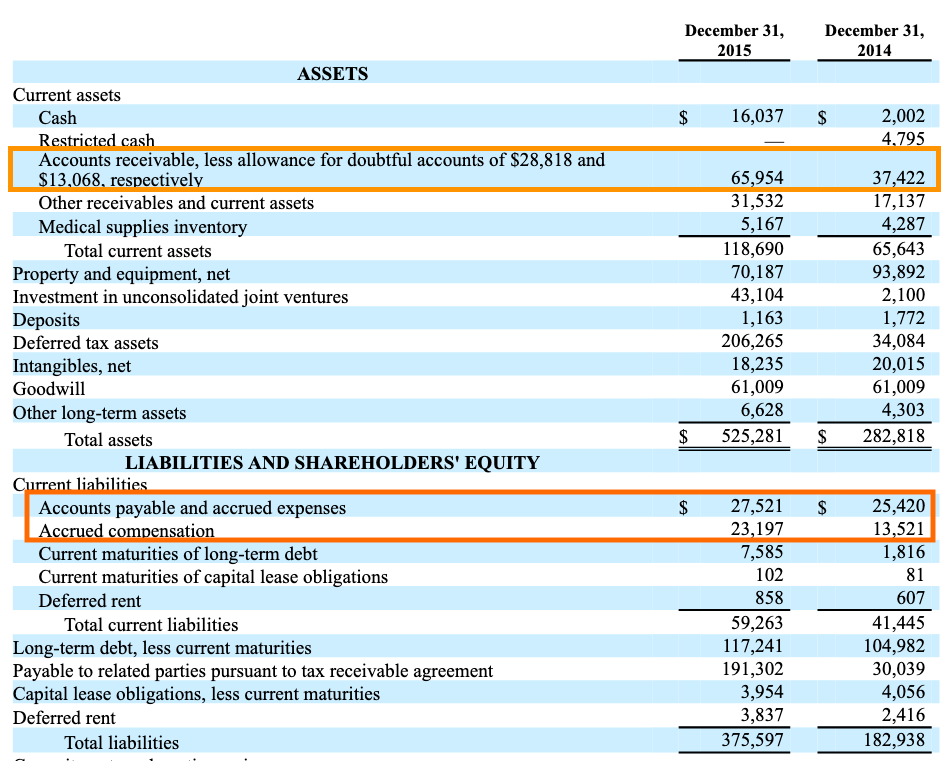

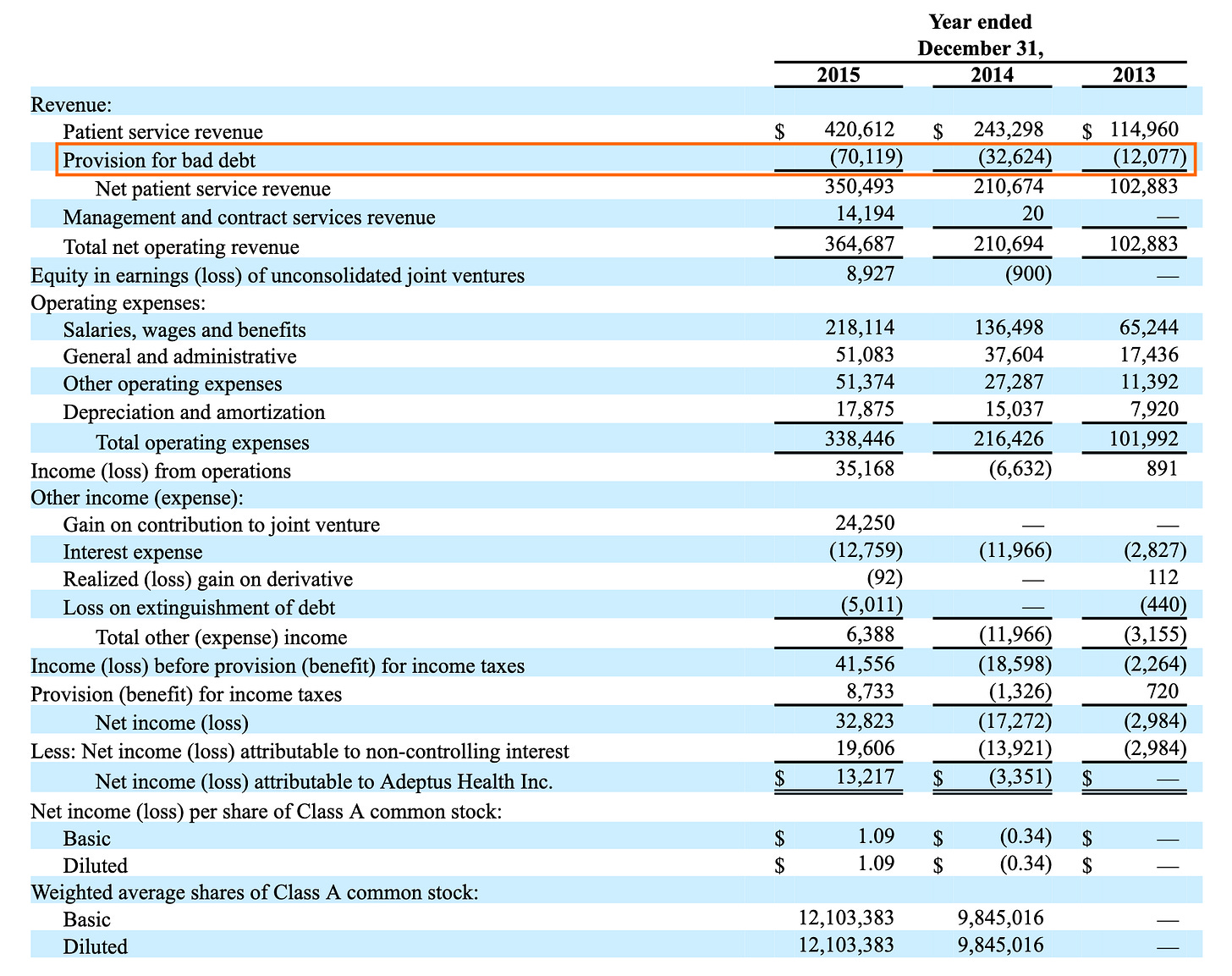

As the likelihood of collecting a significant portion of these aged receivables diminished, Adeptus was forced to take increasingly large charges for bad debt expense (allowance for doubtful accounts). This accounting measure, while necessary, had two negative effects: it directly reduced the company's reported net income, revealing that the "quality" of its revenue was lower than it appeared, and it further spooked investors who saw it as confirmation of the underlying collection problems. The working capital crisis, centered on the unmanageable mountain of accounts receivable, was now becoming undeniable and directly impacting the company's perceived profitability and financial health.

Operational Strain, Reporting Issues, and the Point of No Return

The severe strain on cash flow caused by the A/R crisis inevitably began to impact other areas of the business and attract further scrutiny.

Operational Costs and Leverage: The FSER model, unlike urgent care clinics, carries high fixed operating costs. Adeptus needed to maintain full ER staffing and equipment readiness 24/7, regardless of patient volume at any given moment. This high operational leverage meant the company was extremely sensitive to revenue fluctuations and, critically, to cash collection delays. When cash inflows slowed to a trickle while fixed costs remained high, the liquidity squeeze intensified rapidly.

Pressure on Payables (DPO): While detailed data on Adeptus's DPO trends might be less public, it's highly probable that the company attempted to conserve cash by stretching payments to its own suppliers (medical equipment vendors, pharmaceutical companies, service providers). While potentially offering short-term relief, aggressively delaying payments risks damaging crucial supplier relationships, potentially leading to delivery interruptions or demands for stricter payment terms (like cash-on-delivery), which would further exacerbate the liquidity crisis. It turns a source of financing (supplier credit) into an immediate cash demand.

Inventory Management: Though likely less central than A/R, managing inventory of expensive medical supplies and pharmaceuticals across a large network of facilities also consumes working capital. Inefficiencies here, driven perhaps by inadequate systems or forecasting difficulties, would only add to the cash pressure.

Financial Reporting Scrutiny: The widening gap between recognized revenue and cash collections, along with the escalating bad debt provisions, inevitably drew attention from auditors, analysts, and regulators. Questions arose about the company's revenue recognition policies and the adequacy of its internal controls over financial reporting. In late 2016 and early 2017, Adeptus announced delays in filing its financial reports and eventually signaled the need for significant adjustments and potential restatements related to its revenue cycle management and accounts receivable valuation. These disclosures shattered already fragile investor confidence.

The company found itself trapped. It needed cash desperately, but its core operations weren't generating it fast enough due to collection issues. Its rapidly accumulated assets (the FSER facilities) were expensive to operate and difficult to quickly convert to cash. Its ability to raise further debt was hampered by its already leveraged balance sheet (stemming partly from the IPO-fueled expansion) and mounting operational concerns. Equity financing was effectively closed off as the stock price plummeted following the negative disclosures.

Bankruptcy and the Aftermath

By the spring of 2017, Adeptus Health had run out of options. Unable to meet its financial obligations and facing a full-blown liquidity crisis directly traceable to its inability to manage its receivables and overall working capital cycle, the company filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection.

The bankruptcy proceedings revealed the extent of the financial distress. The goal was to restructure the massive debt load and potentially sell off assets or find a buyer for the entire enterprise. However, the underlying challenges of the FSER model in the face of payer pushback, coupled with the operational inefficiencies and damaged credibility of Adeptus itself, made a successful turnaround difficult.

Ultimately, the existing shareholders were wiped out. Control passed to the company's creditors. Over the following months and years, the Adeptus network was largely dismantled. Many facilities were closed, while others were sold off or fully integrated into the operations of its former hospital partners (who often acquired the JV interests at distressed prices). The pioneering FSER company ceased to exist as an independent entity.

Lessons from the Adeptus Collapse: Working Capital is Not Optional

The dramatic rise and fall of Adeptus Health offers critical lessons, particularly regarding the often-underestimated importance of working capital management.

Revenue Growth Without Cash Flow is Unsustainable: Adeptus demonstrated impressive top-line growth for several years. However, this revenue was not translating into timely cash collections. Investors and managers must always ask: is the reported revenue "high quality"?

Is it collectible?

How long does it take to turn a sale into usable cash (DSO)?

High revenue growth fueled by uncollectible or very slow-paying receivables is a recipe for disaster.

Working Capital Efficiency is Crucial, Especially During Growth: Rapid expansion consumes enormous amounts of cash – for building facilities, hiring staff, and financing the growing base of inventory and receivables. Adeptus's failure to build scalable, efficient back-office operations (especially billing and collections) alongside its physical expansion meant its working capital needs ballooned out of control. Efficient management of the Cash Conversion Cycle (CCC = DII + DSO - DPO) is paramount during growth phases.

Understand the Operational Realities Behind the Numbers: Financial statements can obscure underlying operational problems. Adeptus's reported revenues looked strong initially, but a closer look at the soaring DSO and bad debt provisions would have revealed the collection crisis much earlier. Investors need to dig into the working capital ratios and understand the real-world processes they represent.

Business Models Must Align with Cash Flow Realities: The FSER model's reliance on high, hospital-level reimbursement rates proved difficult to sustain against insurer pushback. The resulting cash collection cycle mismatch made the model inherently risky, especially when coupled with high fixed operating costs and aggressive growth funded by external capital.

Adeptus Health's story is more than just another bankruptcy or a tale of failed disruption. It is a powerful case study in working capital mismanagement and business model. It underscores the fact that profitability on paper is meaningless if a company cannot efficiently manage the flow of cash through its operations. For investors seeking sustainable value, analyzing a company's ability to manage its inventory, collect its receivables promptly, and maintain healthy relationships with its suppliers is not just good practice – it is absolutely essential. Neglecting the intricacies of working capital can, as Adeptus Health tragically demonstrated, lead even the most promising ventures down the path to ruin.

Max